surgery after epidural hematoma and what to exoect

Abstract

Background: The Brain Trauma Foundation's 2006 surgical guidelines have objectively divers the epidural hematoma (EDH) patients who tin exist treated conservatively. Since and then, the literature has not provided adequate clues to place patients who are at higher gamble for EDH progression (EDHP) and conversion to surgical therapy. The goal of our study was to place those patients. Methods: We carried a retrospective review over a 5-yr period of all EDH who were initially triaged for conservative management. Demographic information, injury severity and history, neurological status, utilise of anticoagulants or anti-platelets, radiological parameters, conversion to surgery and its timing, and Glasgow Outcome Scale were analyzed. Bivariate clan and further logistic regression were used to point out the significant predictors of EDHP and conversion to surgery. Results: 125 patients (75% of all EDH) were included. The mean historic period was 39.one years. The encephalon injury was mild in 62.iv% of our sample and severe in fourteen.iv%. But 11.2% of the patients required surgery. Statistical comparison showed that younger age (p< 0.0001) and coagulopathy (p=0.009) were the only significant factors for conversion to surgery. In that location was no divergence in outcomes betwixt patients who had EDHP and those who did not. Conclusions: Well-nigh traumatic EDH are not surgical at presentation. The rate of conversion to surgery is depression. Significant predictors of EDHP are coagulopathy and younger age. These patients need closer observation because of a higher risk of EDHP. Issue of surgical conversion was similar to successful conservative management.

Résumé

Hématome épidural traité de façon conservatrice : quand s'attendre au pire. Contexte : Les lignes directrices chirurgicales de la Brain Trauma Foundation de 2006 ont défini objectivement les patients atteints d'united nations hématome épidural (HÉD) qui peuvent être traités de façon conservatrice. Depuis lors, il due north'existe pas dans la littérature d'indices adéquats pour identifier les patients qui sont à plus haut risque de progression de l'HÉD et chez qui un traitement chirurgical doit être envisagé. Le only de notre étude était d'identifier ces patients. Méthode : Nous avons effectué une revue rétrospective sur une période de five ans des dossiers de tous les patients atteints d'un HÉD qui ont été assignés initialement au traitement conservateur. Nous avons analysé les données démographiques, la sévérité de la lésion et son historique, l'état neurologique, la prise d'anticoagulants ou d'antiplaquettaires, les paramètres radiologiques, le recours à un traitement chirurgical et le moment où il a été réalisé ainsi que le score au Glasgow Issue Scale. L'analyse bivariée ainsi que 50'analyse de régression logistique ont été utilisées pour déterminer les facteurs de prédiction significatifs de la progression de l'HÉD et du recours à la chirurgie. Résultats : Cent vingt-cinq patients (75% des patients atteints d'united nations HÉD) ont été inclus dans fifty'étude. L'âge moyen des patients était de 39,1 ans. La lésion cérébrale était légère chez 62,4% des patients alors qu'elle était sévère chez fourteen,4% d'entre eux. Seulement xi,2% des patients ont nécessité une chirurgie. L'analyse statistique a montré que le jeune âge du patient (p 0,0001) et la présence d'une coagulopathie (p = 0,009) étaient les seuls facteurs significatifs du recours à la chirurgie. Il n'existait pas de différence entre les résultats chez les patients qui avaient eu une progression de l'HÉD et ceux des patients qui n'en avaient pas eu. Conclusions : La plupart des HÉD traumatiques ne requièrent pas de traitement chirurgical initialement. Le taux de recours éventuel à la chirurgie est bas. Les facteurs de prédiction significatifs de la progression de l'HÉD sont la présence d'une coagulopathie et le jeune âge du patient. Ces patients doivent être observés de près car ils sont à risque plus élevé de progression de l'HÉD. Le résultat du recours à la chirurgie était similaire à celui du traitement conservateur lorsque celui-ci était efficace.

This is an open admission article, distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/3.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Epidural hematomas (EDH) represent ii.vii-4% of traumatic brain injuries (TBI)Reference Bullock, Chesnut and Ghajar 1 - Reference Gupta, Tandon, Mohanty, Asthana and Sharma three and take a acme incidence during the 2d life decade.Reference Bullock, Chesnut and Ghajar 1 , Reference Bricolo and Pasut four - Reference van den Brink, Zwienenberg, Zandee, van der Meer, Maas and Avezaat 8 The source of bleeding can be an injured centre meningeal artery, diploic vein or venous sinus.Reference Bullock, Chesnut and Ghajar 1 The Encephalon Trauma Foundation (BTF) surgical guidelines, although based on course Three studies, are widely accepted. They provide objective criteria for deciding either surgical or bourgeois management in EDH patients.Reference Bullock, Chesnut and Ghajar 1 Nonetheless those who are managed non-operatively remain a business concern for the treating neurosurgeon as EDH progression (EDHP) may alter the course of conservative approach. Incidence of EDHP needing surgical intervention is reported to range between half dozen.25-32% of EDH patients treated initially conservatively in larger studies adopting BTF guidelines or, earlier its publication, studies that had more stringent criteria for conservative approach.Reference Bezircioğlu, Erşahin, Demirçivi, Yurt, Dönertaş and Tektaş 9 - Reference Sullivan, Jarvik and Cohen 12 I written report had 23% EDHP in the sample but only ten% required evacuation.Reference Sullivan, Jarvik and Cohen 12 Some other study had 32% of its conservative group (59 patients) complicated with EDHP and 22% of them required surgical intervention.Reference Mayr, Troyer and Kastenberger 10 The other authors had to operate on a single EDHP case each.Reference Bezircioğlu, Erşahin, Demirçivi, Yurt, Dönertaş and Tektaş 9 , Reference Salama and Eissa 11 Epidural hematoma progression represented vii.9% of all cases of TBI progression in a randomized controlled trial.Reference Ding, Yuan and Guo 13 The risk factors of such progression are still non very obvious and the literature has seldom addressed this issue with specific attention and more often than not in studies prior to the publication of the BTF surgical guidelines. Nosotros carried out this study to identify which patients, among those candidates with EDH, suitable for an initial not-operative treatment, are at greater chance of EDHP, and to determine when they become surgical candidates.

Methods

Patient population

The electric current written report is a Case-Control study in which nosotros retrospectively reviewed the charts of TBI patients who were admitted, over a five-year period, to the Montreal General Hospital, a level 1 trauma center, and i of only iii adult level 1 trauma centers serving the province of Quebec, Canada, which has a population of virtually viii one thousand thousand people. Nearly 2800 patients were admitted with a diagnosis of TBI during that five-yr period. The Montreal General Hospital Traumatic Brain Injury Database and the Trauma Registry Database were used to identify all patients admitted betwixt Jan 1st, 2006 and December 31st, 2010 with a diagnosis of traumatic EDH. Our inclusion criteria were: all patients with a traumatic EDH, with or without other brain injury types, for whom bourgeois management arroyo was planned initially. Those who had cranial surgery for a lesion other than EDH on the contrary side were included. Patients who were admitted for urgent surgery, those who were deemed non salvageable at presentation, or those for whom the initial (CT) images were acquired at another institution and were not bachelor for review were excluded. Patients for whom charts were incomplete were also excluded.

Patient management

All patients with a traumatic EDH were evaluated by a dedicated trauma team and past the neurosurgery service. Patients requiring firsthand surgery were directed to the operating room. The study spans a time period shortly earlier the publication and application of the BTF surgical guidelines. Therefore the decision to operate immediately, versus conservative management, was left to the treating neurosurgeon. Patients with small-scale EDH (<30 cm3 ) and no associated midline shift or deficit were initially conservatively treated. They were observed in the emergency department or in the intensive care unit under close monitoring for at least 24 hours. The CT scans were routinely done upon presentation and so routinely repeated inside 6–12 hours and whenever neurological deterioration occurred. Patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit of measurement underwent a second routine follow-up CT scan after 48 hours if venous thrombo-prophylaxis was to exist initiated.

Data collection

The charts were reviewed for demographic data, TBI severity using Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), global injury severity using the Injury Severity Score (ISS), method of injury, neurological status at presentation, employ of anticoagulants or anti-platelet medications, presence of booze intoxication or coagulopathy, divers equally an International Randomized ratio (INR) >i.2, or a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) >50 seconds for the kickoff 24 hours following admission. The CT scans were reviewed to retrieve EDH site and parameters, note any mass event or other cranial injuries and measure the midline shift (MLS). The size of the lesions was collected in three dimensions. The width was measured as the transverse diameter, the length every bit antero-posterior diameter and the depth equally the supero-inferior diameter. For use in the regressions, nosotros computed an approximated volume by multiplying the three dimensions using the equation: volume=ABC/2.Reference Petersen and Espersen 14 The fourth dimension delay between the initial CT and the follow up CT was also recorded

Outcome measures

The master consequence measures were: (ane) the pct of patients initially treated conservatively who required eventual surgical evacuation of their EDH; (two) the timing for that delayed surgery; (iii) the reason for requiring this delayed surgical evacuation; (iv) the method used for surgical evacuation. Secondary issue measure was the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE) scoreReference Jennett and Bond 15 - Reference Jennett, Snoek and Bond xvi at belch from the acute care hospital, whether the discharge destination was home or another medical facility. The GOSE was e'er assigned according to a consensus within the multidisciplinary squad at belch from the astute care hospital.

Statistics

The patients were categorized into two groups: "ascertainment" group with successful conservative approach and "EDHP" group that required urgent surgical evacuation. Subsequently statistically comparing both groups' characteristics, Bivariate Association statistical analysis was used to associate risk factors with EDHP. A logistic regression was run to predict the occurrence of EDPH and subsequent surgery. Subsequently, a stepwise logistic regression (pin<0.05) was used and the significantly different variables were entered in the model. Outcomes were assessed by linear and bivariate regressions using the GOSE calibration.

Results

The demand for surgical evacuation

A total of 201 patients with a diagnosis of EDH were retrieved from our center'due south TBI registry. Of those, 30 were excluded because they had been wrongly labelled as EDH, and 5 were excluded because but condolement measures were offered (2 patients), or the data were incomplete (three patients). Therefore, 166 patients had a diagnosis of traumatic EDH and were actively treated. Of those, 41 required emergency evacuation (24.vii%) and 125 patients (75.3%) were initially observed and were therefore included in the nowadays study. The majority (111 patients or 88.8%) of the patients with EDH who were initially observed remained non-operative, and only fourteen patients (11.2%) required delayed surgery. Therefore, of all the patients with traumatic EDH actively treated, 55 eventually required surgical evacuation of the EDH (33.1%). Figure one illustrates the organisation of the sample.

Figure 1 Distribution of all treated epidural hematoma between immediate surgical treatment, initial conservative handling and failed conservative treatment.

Demographic data (historic period, GCS, ISS, machinery of injury, alcohol intoxication)

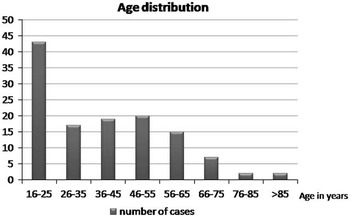

The mean age in the unabridged sample was 39.one+/−18.0 years of age (range 16-96). Figure 2 depicts the age distribution of the sample. Three patients had bilateral EDH. In lodge to avoid having dependence in the sample, but i lesion was chosen randomly in those patients. Men composed the bulk of the sample (81.6%). Glasgow Coma Score at admission varied between 3 and 15 with a mean (±SD) of 12.6±3.iv and a median of 14. The majority of the sample (62.4%) had a mild TBI (GCS later on resuscitation between 13 and 15), and 14.4 % had a severe TBI (GCS 3-8). The average (±SD) ISS score was 27.5±8.six. Sixty-one percent of the sample experienced a loss of consciousness at the fourth dimension of the trauma. Amidst those who did not experience loss of consciousness, 23.4% experienced amnesia. The nearly frequent mechanisms of injury were fall from superlative (27.nine%) and assault (twenty.5%). Tabular array 1 gives the relative incidence of each machinery of injury. Of the 115 patients who take been tested, 40.9% tested positive for claret ethanol.

Figure 2 Distribution of age in the sample.

Table 1 Frequency of machinery of trauma (north=122)

Coagulation

Of the 108 patients who had the information in their nautical chart, 3.vii% were using anti-platelets or anticoagulants only none of them was amongst the EDHP group. Of the 114 patients whose coagulation profiles were tested, 19.3% had coagulation abnormalities.

EDH site and size

A little more than half (56.4%) had a right sided lesion. Most one-half of the lesions were temporal (48.0%) (come across Table 2 for location distribution). The mean (±SD) width, length, depth and volume were 10.2 (±xi.iv) mm, 30.7 (±15.v) mm, 26.2 (±18.ii) mm and nine.788.7 (±15.390.1) cmthree respectively. More 93% of the sample had less than 2mm MLS. A large majority of the patients (72.0%) had related fractures but only v.6% were depressed fractures.

Tabular array two Epidural hematoma location distribution (n=125)

Detection of EDHP

All of the EDHP patients needed evacuation. 5 patients had EDHP detected considering they showed signs of neurological deterioration and a CT was repeated urgently. Even so, EDHP was detected by routine follow upwards CTs in well-nigh of those with mild TBI (half-dozen out of eight patients) and half of those with moderate (two of iv) and severe (i of two) TBI. The initial volume of EDH that eventually progressed was xiii cmthree on average, while the volume at progression was 21 cm3. Time delay for EDHP occurrence ranged between five–30 hours (h) from the initial CT, with a mean time of 12.4h. Two patients had a 30h time interval for the EDHP to progress. I of those 2 actually sought medical attending just two days later the trauma. Hence the progression of EDH in that case was much delayed.

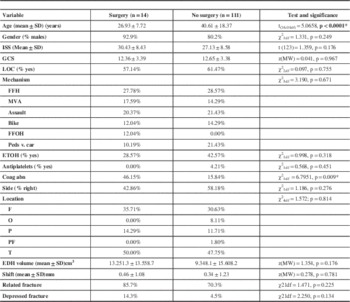

Bivariate associations betwixt patient and trauma characteristics and surgery upshot

The EDHP group who had surgery was significantly younger than the other group (p<0.0001). Among the non-operated patients, 16 out of the 101 tested for coagulation had abnormalities detected (16.7%). This was significantly college in the EDHP group where six of the 13 tested patients (46.one%) had documented coagulation aberration (p=0.009).

In that location were no differences in gender, ISS scores, GCS scores, proportion of loss of consciousness, mechanism of trauma, proportion of presence of alcohol in the blood, proportion of utilize of anticoagulant or anti-platelet therapy, side of the lesion, location of the lesion, midline shift, proportion of associated fractures, proportion of depressed fractures, whatsoever of the dimensions of size or volume of the lesion between the EDHP and non-surgical groups. Table 3 lists all the variables, the statistical test used to compare them and the p values for each.

Table 3 Statistical comparing of surgery v. no surgery groups

Prediction model for EDHP

Historic period was entered as a control variable since the groups had different mean ages. Increasing age decreases the odds of having surgery (odds ratio (OR) =0.94; 95% confidence interval (CI) =[0.91; 0.97]). After controlling for age, having a coagulation aberration increased the odds of having surgery by an average of half-dozen times (OR=6.12, 95% CI=[1.54; 24.36]) but the volume of the lesion was an insignificant predictor. Table 4 shows the exponentiated coefficients (OR) for each variable in the model besides as their significance.

Tabular array iv Results of the logistic regression predicting the result of surgery

Figure iii shows the ROC curve of this regression model. The area under the curve is 0.813 and is significantly larger than 0.5, indicating those variables are important predictors of the occurrence of surgery. A sensitivity/specificity plot equally in Effigy four shows that when the probability of surgery is larger than 12.5% using the three variables in the logistic regression, the sensitivity of the predictive model is 77% and the specificity is eighty%.

Figure 3 Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the prediction of surgery using the three variables (age, aberrant coagulation and hematoma volume) model. The full number of patient is 113 as coagulation as all three variables were known in 113 patients.

Figure 4 Sensitivity and specificity plot co-ordinate to the probability of surgery.

Outcome

Seven patients (five.vi%) died and a small proportion of subjects had severe disability (7.2%). The majority of the sample (87.ii%) had a good recovery (GOSE between 5 and vii) early in development. Table 5 gives the distribution of the GOSE scores.

Table 5 Frequency of GOS scores (n=125)

Having progression of the EDH was not associated (χ2 KW1df=0.318, p=0.5730) with a better or worse upshot (GOSE score). Even when controlling for historic period, coagulation abnormality and book of the lesion, having EDHP was not a significant predictor of the event in an ordinal logistic regression (OR=0.644, p=0.604).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that, contrary to mutual conventionalities, the majority of traumatic EDH are not surgical emergencies with 75% of the cases initially treated conservatively. Furthermore, even when bookkeeping for EDHP, ii thirds of the EDH patients never required surgery. The main factors leading to EDHP found in this written report were a younger age and coagulation abnormalities during the first 24 hours subsequently presentation.

Risk factors for EDHP

The causes of EDHP have not been well studied. A recent randomized control trial (RCT)Reference Ding, Yuan and Guo 13 examined the office of routine series CT scans in TBI and reported that 79 patients (46.two% of the sample) had progression of TBI, but only ten of these 79 had EDH (7.nine%). Their sample too included delayed onset of hematomas. The latter should be better considered a different categoryReference Sullivan, Jarvik and Cohen 12 , Reference Domenicucci, Signorini, Strzelecki and Delfini 17 and is outside the spectrum of our study. Risk factors for all hematomas progression were: higher D-dimer concentration, lower GCS on presentation, higher INR and to a lesser extent, shorter time lapse between trauma onset and initial CT. The finding of abnormality in coagulation contour correlates with our report. Bhau et alReference Bhau, Bhau, Dhar, Kachroo, Babu and Chrungoo 18 quoted a charge per unit of 25% of patients who failed conservative handling out of 89 patients simply likewise did not differentiate EDHP from delayed onset EDH and reported no statistical analysis of potential risk factors for progression. A prospective seriesReference Bezircioğlu, Erşahin, Demirçivi, Yurt, Dönertaş and Tektaş 9 of eighty EDH patients of volume <30 ml treated conservatively concluded that in the 5 patients (6.25%) who developed EDHP, the only significant association was temporal location. This could be overestimated because of the smaller number and exclusively temporally located cases of EDHP. Sullivan et al,Reference Sullivan, Jarvik and Cohen 12 in a retrospective study of 160 patients treated conservatively, found only higher revised trauma score (implying mild multisystem injury) to exist significantly correlated to EDHP. In our study, ISS had no correlation to EDHP. Another pocket-sized retrospective written reportReference Knuckey, Gelbard and Epstein 19 reported 7 of 22 patients developed EDHP. Initial CT<half-dozen hours from onset of trauma and skull fractures traversing major vascular structures were significant risk factors in that report. Injury to commencement CT time lapse was non investigated in our study. The pregnant correlation with younger age in our written report is a new finding, still it is not surprising. Indeed, it could exist explained by the fact that, in older people, dura matter is more adherent to the internal table of the skull, leaving a faster tamponade effect and less potential epidural space in which the EDH may accumulate. Why it was not picked upwards in previous studies is not clear but i possible reason might be that our study includes patients of all ages, with a wide range of distribution and non but younger people. Finally, the book of the hematoma was not a predictor of progression in our study, nor was it in any of the other studies. This is probable due to the fact that all hematomas treated conservatively were of modest size.

Timing of follow upward CT scans

The literature is non in favor of routine follow up CTs in mild TBI, as a recent meta-assayReference Almenawer, Bogza and Yarascavitch 20 revealed, but does recommend information technology for moderate and severe TBI. The question of optimal timing for follow upwardly CTs remains, however, unanswered.Reference Ding, Yuan and Guo thirteen , Reference AbdelFattah, Eastman and Aldy 21 - Reference Sifri, Homnick and Vaynman 23 In their RCT, Ding et al.Reference Ding, Yuan and Guo 13 performed serial follow up CTs, scheduled as follows: 6-8h, 20-22h, 48h and seven days for i TBI group and only when neurologically indicated for the controls. This resulted in significantly shorter stay in intensive care and full infirmary stay, better GCS at belch, and less spending among patients who adult progression of injury in the intervention arm. They recommended restricting routine CTs to patients with moderate or severe TBI. Some other prospective cohort of mild TBI reported that infirmary stay is reduced if CT scans were done only when clinically dictated.Reference AbdelFattah, Eastman and Aldy 21 Figget et al.Reference Figg, Burry and Vander Kolk 24 found, in a retrospective series, that echo CT scan after 24-48 h doesn't alter the management of astringent nonsurgical TBI. Our written report shows that most EDH patients treated conservatively according to the BTF guidelines had mild TBI. Near of our EDHP cases with initial balmy TBI were diagnosed for progression on planned follow up scans. This may advise that EDH should be considered a different subcategory of mild TBI in terms of necessity for routine serial CT scans follow up.

Fourth dimension interval for EDHP

Progression of initially non-surgical EDH generally occurs within the first 24h, less likely within 48h and rarely across that. Yet, it did not occur earlier at least five hours. As identifying the actual injury time cannot exist verified in many trauma cases, we supposed that the time elapsed from the initial CT was more practical. The Ding et alReference Ding, Yuan and Guo 13 RCT reported that lxxx% of patients (56 out of 70) complicated with progression of TBI did so inside 24h and the remaining 20% were delayed 24-48 h. Epidural hematoma, non-operatively treated in accordance with the guidelines, in a prospective non-controlled study,Reference Salama and Eissa eleven accept shown EDHP in 10% of patients, occurring within 12h in vi out of 70 patients and 24 h in ane patient. However, they excluded another patient who developed EDHP later four days. In their larger study, Sullivan et al.Reference Sullivan, Jarvik and Cohen 12 had all EDHP diagnosed within 36 h interval from trauma onset and mean of 5.3 h from the initial CT browse. The smaller study of Knuckey et al.Reference Knuckey, Gelbard and Epstein 19 mentioned a mean time for EDHP of 2.seven days subsequently access (range of 1-10 days) in 7 of 22 patients. The critical period in their opinion was the kickoff 24h (71% of EDHP in their sample). Our EDHP events ranged from 5 to 30 h (mean 13.85h) later the initial CT.

Coagulopathy and EDHP

Coagulopathy has been shown to cause progression of TBI. Recently, a retrospective reportReference Mayr, Troyer and Kastenberger 10 investigated the impact of coagulopathy on EDH outcomes of 85 patients, triaged in compliance with the BTF guidelines, into surgical and conservative groups. It showed a significant negative influence of coagulopathy on the outcomes of both groups but establish no correlation with EDHP. This result is questionable when because the smaller sample number and lack of multivariate analysis. There are variable data in the literature and unlike studies associated one or more than of the following with TBI progression: Prothrombin time (PT) or INR, Partial thromboplastin time (PTT), thrombocytopenia, high fibrin degradation and depression fibrinogen levels.Reference Allard, Scarpelini and Rhind 25 - Reference Stein, Immature, Talucci, Greenbaum and Ross 30 Fewer other studies reported no association between coagulopathy and bleeding progression in TBI.Reference Chang, Meeker and Holland 31 - Reference Sawada, Sadamitsu, Sakamoto, Ikemura, Yoshioka and Sugimoto 33 This considerable variation is attributed to lack of consensus on TBI-coagulopathy definition, heterogeneity of patients involved, variable laboratory tests used in different studies and timing to perform these tests and CTs.Reference Laroche, Kutcher, Huang, Cohen and Manley 34 - Reference Zhang, Jiang, Liu, Watkins, Zhang and Dong 35 The presence of hypodense areas within the epidural hematoma on CT browse is thought to be related to coagulopathy,Reference Hamilton and Wallace 36 yet its association with EDHP is lacking adequate investigations.

TBI associated coagulopathy

Well-nigh half of our EDHP patients had coagulopathy, despite the fact that none of the patients (one with missing information) were on anti-platelet or anticoagulation medication. This raises the suspicion of TBI-associated coagulopathy, which has an uncertain pathophysiology.Reference Laroche, Kutcher, Huang, Cohen and Manley 34 - Reference Zhang, Jiang, Liu, Watkins, Zhang and Dong 35 The overall incidence of TBI-associated coagulopathy in a meta-assay was 32.7% and was significantly associated with bloodshed and unfavorable outcome.Reference Harhangi, Kompanje, Leebeek and Maas 37 A multicenter prospective report reported that within 6h from injury, 36% of its TBI sample fulfilled the criteria for overt disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) which proved to have a significant correlation with hemorrhage progression. All other causes of coagulopathy were excluded in that report.Reference Dominicus, Wang and Wu 38 A more recent multicenter studyReference Franschman, Boer and Andriessen 39 demonstrated that both delayed and early sustained coagulopathy in isolated TBI correlates with more than abnormalities on initial CT, hematomas >25 ml and worse outcomes in comparison with early on short-term coagulopathy.

Outcome

The crusade of EDHP is supposedly a re-hemorrhage upshot or continuous slow bleeding.Reference Sullivan, Jarvik and Cohen 12 , Reference Bhau, Bhau, Dhar, Kachroo, Babu and Chrungoo 18 Encephalon Trauma Foundation guidelines for successful EDH bourgeois management states that: "An EDH less than thirty cm3 and with less than a 15-mm thickness and with less than a 5-mm midline shift (MLS) in patients with a GCS score greater than 8 without focal arrears can exist managed not-operatively with serial computed tomography (CT) scanning and close neurological observation in a neurosurgical center".Reference van den Brink, Zwienenberg, Zandee, van der Meer, Maas and Avezaat 8 The rubber of these guidelines for conservative handling of EDH was recently tested in a prospective non-controlled report of seventy patients which showed its safety just emphasized the need for shut observation and serial CT scans.Reference Salama and Eissa 11 Encephalon Trauma Foundation guidelines proved to exist safe and provided practiced outcomes for EDH patients treated conservatively. Should EDHP develop, then timely surgical intervention can maintain like outcomes to the successful conservatively treated counterparts, as this study and all other related studies have shown.Reference Mayr, Troyer and Kastenberger x - Reference Sullivan, Jarvik and Cohen 12

The early outcome of our accomplice was favorable for the great majority. A pocket-sized number died or had astringent disability. A poor outcome was not linked to EDH progression however, but rather to the patients' initial injury severity and older historic period.

Limitations of our study include its retrospective nature and a small number of patients with missing data. On the other hand, the research question was very specific and the sample number was adequate to perform statistical comparison and multivariate assay. Another limitation of our study is that the effect was measured systematically for all patients early in the development of the patients (at discharge from astute intendance hospital). While almost of the patients already fell into the category of "adept outcome", the long term outcome would probable be better withal.

Furthermore, all patients with EDH were included in this study, and patients with concomitant injuries were included besides. The patients' consequence could therefore be influenced by the severity of the initial injury and non only by the EDH. The advantage of including patients with concomitant injuries in this study is that the results tin be extrapolated to all patients with EDH and not merely those with pure EDH, as the latter category does not in fact represent the majority of EDH seen in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Traumatic EDH tin can be successfully treated conservatively in the bulk of cases. A small proportion of these non-surgical EDH will progress and require surgical evacuation. Increased vigilance is indicated for younger adults and those with coagulopathy. Routine follow up CT scans should be done, just the best time frame remains unclear. Nevertheless, early detection of EDHP and urgent evacuation results in similar outcomes to patients with fully successful conservative management.

Disclosures

None of the authors have anything to disclose.

None of the authors take any competing fiscal interests.

References

1. Bullock, MR , Chesnut, R , Ghajar, J , et al. Surgical management of acute epidural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(Suppl):S7-S15.Google Scholar

ii. Cordobes, F , Lobato, RD , Rivas, J , et al. Observations on 82 patients with extradural hematoma. Comparison of results before and later on the appearance of computerized tomography. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:179-186.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

3. Gupta, South , Tandon, SC , Mohanty, S , Asthana, South , Sharma, S . Bilateral traumatic extradural haematomas: Report of 12 cases with a review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1992;94:127-131.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

4. Bricolo, AP , Pasut, LM . Extradural hematoma: toward zero bloodshed. A prospective study. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:8-12.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

5. Cucciniello, B , Martellotta, N , Nigro, D , Citro, Eastward . Conservative management of extradural haematomas. Acta Neurochir. 1993;120:47-52.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

half dozen. Kuday, C , Uzan, M , Hanci, 1000 . Statistical analysis of the factors affecting the outcome of extradural haematomas: 115 cases. Acta Neurochir. 1994;131:203-206.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

vii. Lee, EJ , Hung, YC , Wang, LC , Chung, KC , Chen, HH . Factors influencing the functional outcome of patients with acute epidural hematomas: Analysis of 200 patients undergoing surgery. J Trauma. 1998;45:946-952.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

8. van den Brink, WA , Zwienenberg, M , Zandee, SM , van der Meer, 50 , Maas, AI , Avezaat, CJ . The prognostic importance of the volume of traumatic epidural and subdural haematomas revisited. Acta Neurochir. 1999;141:509-514.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

9. Bezircioğlu, H , Erşahin, Y , Demirçivi, F , Yurt, I , Dönertaş, K , Tektaş, S . Nonoperative handling of acute extradural hematomas: analysis of 80 cases. J Trauma. 1996;41:696-698.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

x. Mayr, R , Troyer, South , Kastenberger, T , et al. The impact of coagulopathy on the outcome of traumatic epidural hematoma. Curvation Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:1445-1450.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

xi. Salama, MM , Eissa, EM. Conservative Management of Extradural Hematoma: Experience with 70 Cases. Egyptian J Neurol Surgeons. 2010;25:185-194.Google Scholar

12. Sullivan, TP , Jarvik, JG , Cohen, WA . Follow-up of conservatively managed epidural hematomas: Implications for timing of repeat CT. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:107-113.Google ScholarPubMed

13. Ding, J , Yuan, F , Guo, Y , et al. A prospective clinical written report of routine repeat computed tomography (CT) later traumatic brain injury (TBI). Brain Inj. 2013;26:1211-1216.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

fourteen. Petersen, OF , Espersen, JO . Extradural hematomas: measurement of size by volume summation on CT scanning. Neuroradiology. 1984;26:363-367.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

xv. Jennett, B , Bond, K . Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage: a applied calibration. Lancet. 1975;i:480-484.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

16. Jennett, B , Snoek, J , Bail, MR . Inability afterwards severe head injury: observations on the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.. 1981;44:285-293.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

17. Domenicucci, M , Signorini, P , Strzelecki, J , Delfini, R. Delayed post-traumatic epidural hematoma. A review. Neurosurg Rev. 1995;18:109-122.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

18. Bhau, KS , Bhau, SS , Dhar, S , Kachroo, SL , Babu, ML , Chrungoo, RK . Traumatic extradural hematoma role of nonsurgical management and reasons for conversion. Indian J Surg. 2010;72:124-129.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

xix. Knuckey, NW , Gelbard, S , Epstein, MH . The management of "asymptomatic" epidural hematomas. A prospective study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70(three):392-396.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

20. Almenawer, SA , Bogza, I , Yarascavitch, B , et al. The value of scheduled repeat cranial computed tomography later on mild head injury: single-center series and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:56-62.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

21. AbdelFattah, KR , Eastman, AL , Aldy, KN , et al. A prospective evaluation of the utilize of routine repeat cranial CT scans in patients with intracranial hemorrhage and GCS score of thirteen to 15. J Trauma Astute Care Surg. 2013;73:685-688.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

22. Brown, CV , Zada, G , Salim, A , et al. Indications for routine echo head computed tomography (CT) stratified by severity of traumatic brain injur. J Trauma. 2007;62:1339-1344.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

23. Sifri, ZC , Homnick, A , Vaynman, A , et al. A prospective evaluation of the value of repeat cranial computed tomography in patients with minimal head injury and an intracranial bleed. J Trauma. 2006;61:862-867.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

24. Figg, RE , Burry, TS , Vander Kolk, WE . Clinical efficacy of series computed tomographic scanning in severe closed head injury patients. J Trauma. 2003;55:1061-1064.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

25. Allard, CB , Scarpelini, S , Rhind, SG , et al. Abnormal coagulation tests are associated with progression of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2009;67:959-967.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

26. Kaufman, HH , Moake, JL , Olson, JD , et al. Delayed and recurrent intracranial hematomas related to disseminated intravascular clotting and fibrinolysis in head injury. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:445-449.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

27. Kumura, E , Sato, Chiliad , Fukuda, A , Takemoto, Y , Tanaka, South , Kohama, A . Coagulation disorders following acute head injury. Acta Neurochir. 1987;85:23-28.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

28. Oertel, K , Kelly, D , McArthur, D , et al. Progressive hemorrhage afterwards head trauma: predictors and consequences of the evolving injury. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:109-116.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

29. Stein, SC , Spettell, C , Young, G , Ross, SE . Delayed and progressive brain injury in closed-head trauma: radiological demonstration. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:25-xxx.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

30. Stein, SC , Young, G , Talucci, RC , Greenbaum, BH , Ross, SE . Delayed brain injury after caput trauma: significance of coagulopathy. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:160-165.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

31. Chang, EF , Meeker, Thou , Holland, MC . Acute traumatic intraparenchymal hemorrhage: risk factors for progression in the early mail service-injury flow. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:647-656.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

32. Crone, KR , Lee, KS , Kelly, DL Jr . Correlation of admission fibrin deposition products with outcome and respiratory failure in patients with severe head injury. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:532-536.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

33. Sawada, Y , Sadamitsu, D , Sakamoto, T , Ikemura, K , Yoshioka, T , Sugimoto, T . Lack of correlation between delayed traumatic intracerebral haematoma and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:1125-1127.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

34. Laroche, M , Kutcher, M , Huang, MC , Cohen, MJ , Manley, GT . Coagulopathy after traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:1334-1345.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

35. Zhang, J , Jiang, R , Liu, Fifty , Watkins, T , Zhang, F , Dong, JF . Traumatic brain injury-associated coagulopathy. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:2597-2605.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

36. Hamilton, M , Wallace, C . Nonoperative management of acute epidural hematoma diagnosed by CT: The neuroradiologist's office. Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;thirteen:853-859.Google ScholarPubMed

37. Harhangi, BS , Kompanje, E , Leebeek, FW , Maas, AI . Coagulation disorders after traumatic encephalon injury. Acta Neurochir. 2008;150:165-175.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

38. Sun, Y , Wang, J , Wu, X , et al. Validating the incidence of coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with traumatic brain injury-analysis of 242 cases. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:363-368.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

39. Franschman, G , Boer, C , Andriessen, TM , et al. Multicenter evaluation of the course of coagulopathy in patients with isolated traumatic encephalon injury: relation to CT characteristics and upshot. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:128-136.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/canadian-journal-of-neurological-sciences/article/epidural-hematoma-treated-conservatively-when-to-expect-the-worst/38C864C7FE1110B3B0211EFEA13B62F8

0 Response to "surgery after epidural hematoma and what to exoect"

Enregistrer un commentaire